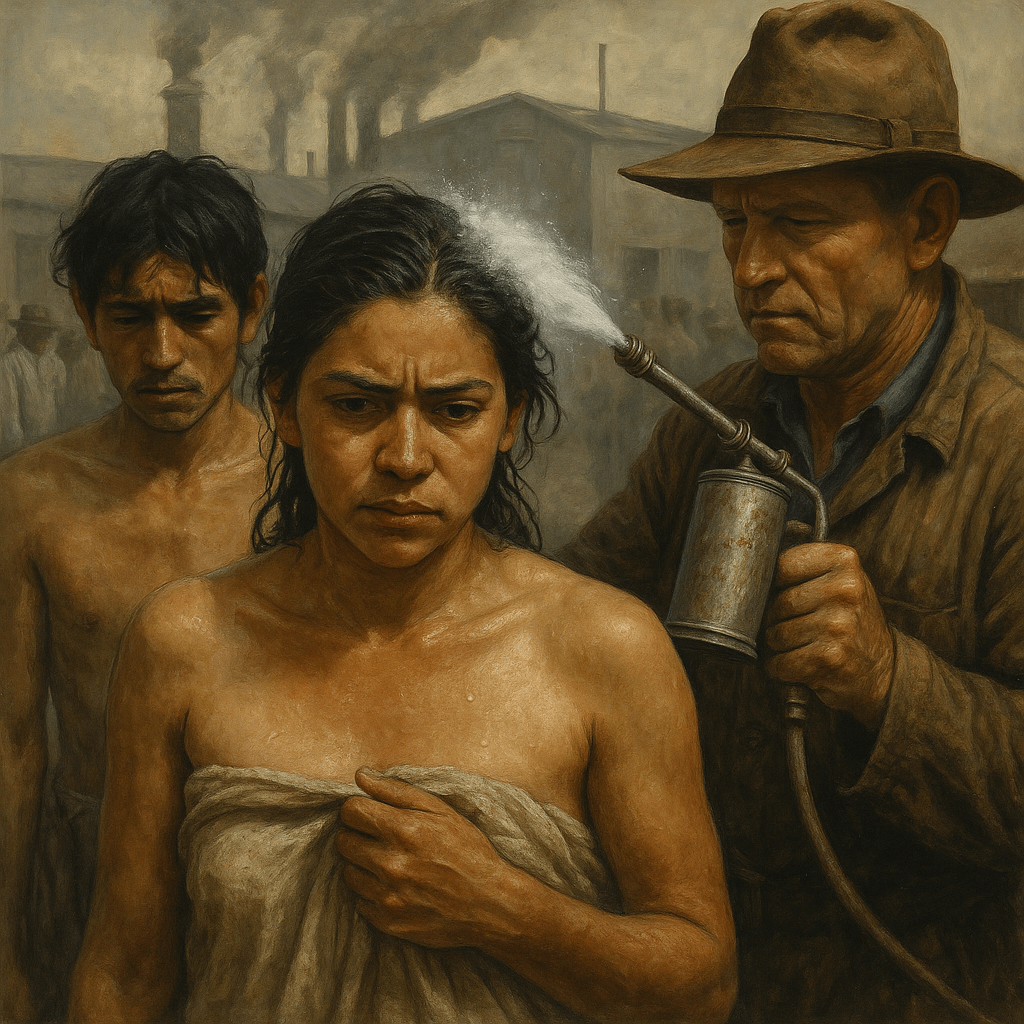

1917: The Bath Riots

In January 1917, Mexican workers commuting across the Santa Fe Street Bridge into El Paso were met with a new U.S. immigration policy: forced disinfection. Men, women, and children were ordered to undress, surrender their clothing to be steamed or fumigated with cyanide gas, and submit to kerosene baths and lice inspections.

Authorities claimed it was about stopping typhus. But the process was degrading and dangerous. Nude photographs of women were rumored to circulate among border guards. A year earlier, 28 inmates at the El Paso jail had burned alive when a gasoline bath ignited.

On January 28, 1917, 17-year-old Carmelita Torres refused. She stepped off the trolley she took to her job as a maid in El Paso and convinced others to resist. For three days, thousands protested on the bridge. The uprising, later called the Bath Riots, was crushed by soldiers, and Torres disappeared into history, erased despite her courage.

The fumigations, however, continued for decades. By the 1920s and 1930s, U.S. border stations were operating cyanide fumigation chambers to treat migrants’ clothing. These practices, developed years before Nazi Germany adopted similar chemical methods under the trade name Zyklon B, cast Mexican bodies as vectors of disease and inferiority. What was framed as “public health” was really about control and humiliation.

1942–1964: The Bracero Program

World War II brought a new labor crisis. With millions of Americans drafted, U.S. agriculture faced a labor shortage. The answer was the Bracero Program, created in 1942 through a bilateral agreement with Mexico. Over the next 22 years, more than 4.6 million Mexican men entered the United States on temporary contracts, the largest guest-worker program in American history.

On paper, braceros were promised fair wages, housing, and protection from discrimination. In practice, most experienced exploitation and abuse:

- Withheld wages that were never returned.

- Overcrowded, unsanitary camps instead of decent housing.

- Segregation and exclusion from “whites-only” facilities.

- Exhausting work under harsh and unsafe conditions.

And just like in 1917, humiliation began at the border. At reception centers, braceros were stripped, inspected like livestock, sprayed with DDT pesticide, and had their clothing fumigated in cyanide chambers. Men recalled being handled “like animals.” Survivors later described long-term health effects from pesticide exposure.

The Bracero Program institutionalized the same logic as the delousing baths: Mexican labor was wanted, Mexican people were not. The state treated workers as disposable bodies useful in the fields, stripped of dignity at the gates.

The Legacy

The fumigation rituals of 1917 and the Bracero years were not just side notes in border history. They were blueprints for racialized labor control. The continuity is striking:

- 1917: Mexicans stripped and scrubbed with gasoline, vinegar, and kerosene.

- 1920s–30s: Border stations deploy cyanide gas chambers for clothing.

- 1940s–1960s: Braceros sprayed with DDT and processed through fumigation centers.

In each case, the state rationalized the abuse as a means to prevent typhus, a wartime necessity, and maintain agricultural stability. And in each case, dignity was sacrificed to maintain a racial hierarchy: Mexican labor was imported when needed, degraded at entry, and discarded when no longer useful.

Carmelita Torres, the teenager who refused to be bathed like an animal, has been called the “Mexican Rosa Parks.” But unlike Rosa Parks, she is mostly forgotten. Her defiance, however, reminds us that resistance has always been present, even when it has been erased from the record.

The Bracero Program ended in 1964, but its lessons remain. It showed that U.S. prosperity was built, in part, on the backs of workers treated as less than human. And it showed how easily dignity can be stripped when policy is guided not by justice but by expediency.

Conclusion

The story of gasoline baths and the Bracero Program is not an aberration; it’s a pattern. From the bathhouses of El Paso to the processing centers of California, Mexican workers were subjected to dehumanization long before they ever set foot in the fields.

America’s food system owes them recognition, not silence. To remember their suffering is to confront the uncomfortable truth: for over half a century, U.S. policy managed Mexican labor through humiliation, chemicals, and broken promises.

Leave a comment