When most people hear “PTSD” and “military,” they think of combat. Firefights, explosions, and battlefield trauma dominate the public imagination. But trauma inside the military does not begin or end with combat. The lifestyle itself, the conditioning, the constant readiness, and the repeated separations can leave deep psychological marks that never make the news.

I served from 1984 to 1992. It was a strange, often forgotten period in military history. The Cold War was ending. The Berlin Wall fell. The services were downsizing. Separation bonuses were offered as the military shifted toward a “post–Cold War” world. Then, almost overnight, the first Gulf War began, and the entire posture flipped from drawdown to mobilization. Even for those of us who never deployed, that uncertainty shaped our nervous systems and our families more than people realize.

The Weight of Training

Military training is built to wire the body for survival. Stress hormones surge. The brain learns to react before thought. Even when the danger is simulated, the reactions are real. Hypervigilance becomes a habit that does not disappear with the end of an exercise.

When I was stationed overseas, that training showed up in ways civilians never see. A ringing phone at two or three in the morning sent me straight into alert mode. Those were the hours when real-world alerts normally came. My heart would pound before I was even fully awake. More than once, it turned out to be my mother calling in a panic over something she saw on the news, unaware of the time difference. I had to calm her down while my own body tried to come down from a false alarm. That is conditioning, not imagination.

The Strain of Separation

Service life is built on goodbyes. Thirty-day training. Forty-five-day rotations. 6-month deployments. Uprooting yourself and family every couple of years. Sudden departures. You detach because you have to. Families adjust because they must. Coming home is never as simple as walking through a door. Reintegration is awkward. Familiar things feel slightly off. You feel like a guest in your own home until the rhythm returns.

Those disruptions leave psychological impressions even when no deployment or combat is involved. They shape relationships, trust, stability, and a sense of belonging.

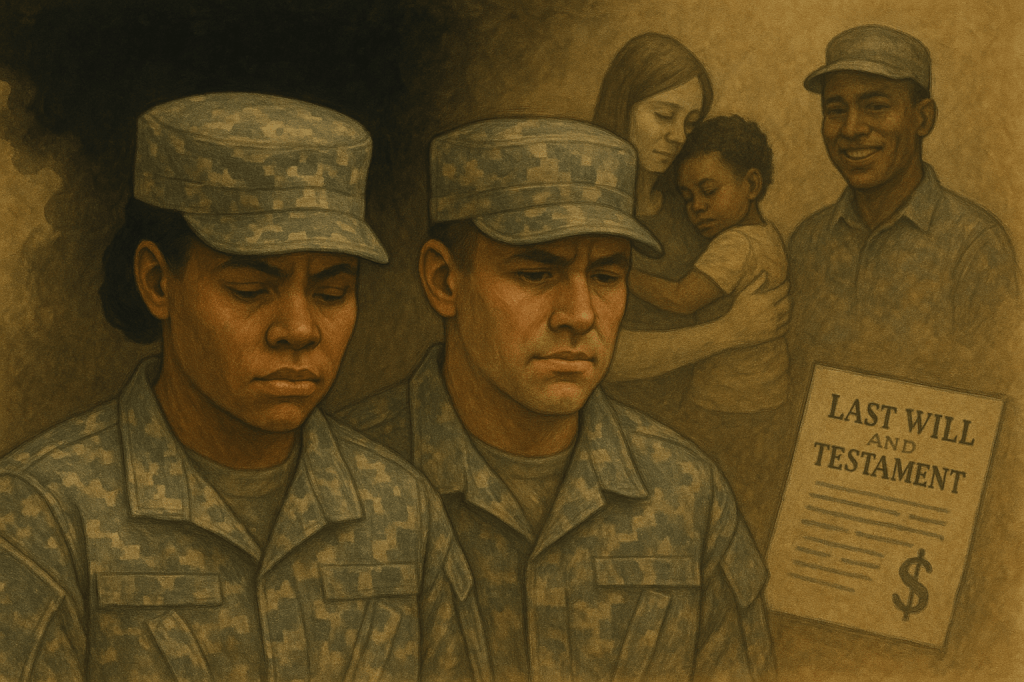

The Administrative Confrontation With Mortality

Every mobilization requires paperwork most civilians do not face until late in life: wills, powers of attorney, life insurance updates, and family contingency plans. During my service, I filled out those forms more than once. The ritual forces you to confront your own mortality in a quiet, procedural way. That burden does not disappear just because your orders never sent you to a hostile fire zone.

Trauma Without Combat

Research supports what many non-combat veterans know firsthand. PTSD symptoms do not arise only from firefights. Hypervigilance, heightened startle responses, detachment, nightmares, and anxiety can develop from training stress, family disruption, constant readiness, and the uncertainty built into military structure. Trauma in the military is not singular. It is a spectrum, and it includes the invisible stressors most civilians never think about.

A Forgotten Window of Service

Those of us who served during the 1984–1992 period sit in a gap between major conflicts. We were not part of Vietnam, and we left before the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began. The public does not think much about that era. But the psychological impact was real. We lived through a drawdown, a sudden war, and years of being trained for a mission that might arrive at any moment.

The moment a person raises their right hand, they give the government a blank check it can cash at any time. Job title and deployment history do not change the weight of that commitment. The stress it carries deserves acknowledgment.

Closing Thought

The hidden wounds of military service do not come only from bullets or bombs. They come from separation, conditioning, disrupted stability, and the strain of always being ready for a moment that may never come. To ignore these experiences is to misunderstand the true cost of wearing the uniform.

Leave a comment