Introduction

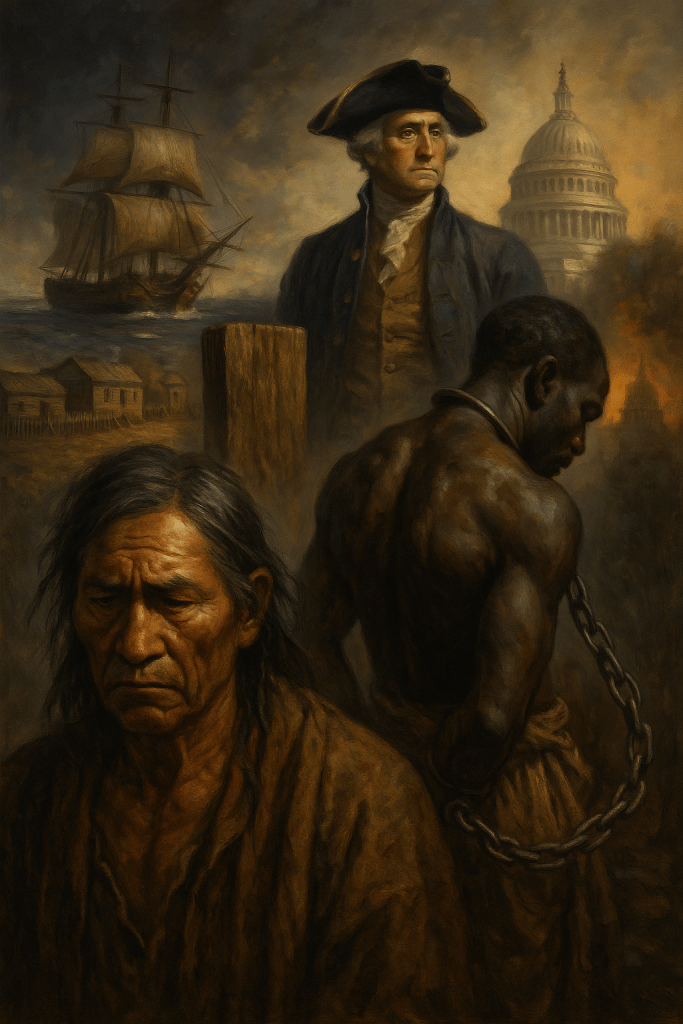

When we think of American history, the usual stories are about freedom, democracy, and progress. But the real foundation beneath the nation’s creation is far darker and more brutal. America’s early economy and political system were built on the ruthless extraction of wealth through the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, the enslavement of Africans, and the violent expansion of land for profit.

This article, drawing on the incisive scholarship of Dr. Roy Casagranda, peels back the sanitized narrative to expose how these forces shaped not just a country, but a system designed to concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a few. From the earliest days of colonial settlement through the birth of capitalism and the framing of the U.S. Constitution, the story is one of economic greed, political control, and systemic inequality.

Understanding this history is essential, not just as a record of the past, but to grasp the roots of the social and racial inequities still embedded in American society today. The sections that follow lay out this history in detail, revealing the calculated structures and harsh realities that formed the backbone of the United States.

1. Colonial America’s Ruthless Drive for Wealth Extraction

From the very moment European ships landed on North American shores, the primary objective of the colonizers was brutally clear: extract as much wealth as possible, by any means necessary. This was not a benign process of settlement or cultural exchange but a systematic, ruthless campaign of dispossession, exploitation, and dehumanization.

Indigenous Dispossession

The Indigenous peoples who had stewarded these lands for thousands of years found themselves immediately under siege. Their relationships with the land—spiritual, economic, and communal—were ignored or deliberately erased. Without consent or recognition of their sovereignty, European settlers claimed vast territories as their own. These lands were not empty wilderness but home to complex societies with rich cultures, economies, and governance.

- Colonial authorities instituted legal frameworks and military force to legitimize and enforce Indigenous dispossession.

- Entire communities were displaced, forcibly relocated, or killed in violent confrontations that colonial powers justified as necessary for “civilization” and economic development.

The Brutality of the African Slave Trade

Parallel to land theft was the horrifying transatlantic slave trade, an enterprise fueled by merciless profit motives. Millions of Africans were torn from their homes, subjected to the inhuman horrors of the Middle Passage, a voyage marked by overcrowding, disease, starvation, and death.

- Mortality rates during the journey were staggering, with some estimates suggesting that 15-20% of enslaved people died en route.

- Survivors were sold into lifelong chattel slavery, stripped of any legal personhood or rights.

- The system codified racial hierarchies, justifying the subjugation and exploitation of Black bodies as natural and necessary for economic gain.

Human Commodification as Economic Strategy

The colonial economy did not merely tolerate this brutality; it depended on it. Enslaved Africans were not viewed as human beings but as commodity units of labor to be bought, sold, exploited, and discarded. This commodification was foundational to the wealth accumulation of colonial elites and the emerging capitalist economy.

- Laws and social norms institutionalized this dehumanization, stripping enslaved people of family bonds, autonomy, and identity.

- Enslaved labor powered plantations, infrastructure, and the transatlantic economy, creating fortunes for a minority while inflicting immense suffering on millions.

Profit Over Humanity

Dr. Roy Casagranda emphasizes that economic profit was the engine driving these systems, not any ethical or humanitarian considerations. Every legal, social, and political decision served to maximize the extraction of value from land and labor.

- The colonists’ moral justifications, such as the “civilizing mission” or religious sanction, were convenient rationalizations masking the underlying economic imperatives.

- The prioritization of wealth extraction normalized violence, dispossession, and systemic inequality as necessary costs of empire-building.

This ruthless foundation of wealth extraction set the stage for environmental exploitation that would transform the land itself and escalate the conflicts that shaped America’s expansion.

This ruthless foundation of wealth extraction set the stage for environmental exploitation that would transform the land itself and escalate the conflicts that shaped America’s expansion.

2. Environmental Destruction and the Westward Expansion Imperative

The economic engine of colonial America, especially in the southern colonies, revolved around the cultivation of tobacco and cotton crops that were both labor-intensive and ecologically devastating. These crops were highly profitable but came with a severe environmental cost that shaped the trajectory of American expansion and conflict.

Ecological Impact of Cash Crops

Tobacco and cotton are notorious for rapidly depleting soil nutrients, unlike many traditional agricultural practices that emphasized crop rotation or soil preservation, colonial plantations operated with a single-minded focus on maximizing short-term yields.

- Tobacco cultivation exhausts the soil’s nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus levels quickly, leading to significant declines in fertility after only a few seasons.

- Cotton, similarly, was hard on the land, requiring intensive inputs and frequent clearing of new plots.

- Planters had little knowledge or willingness to invest in soil conservation techniques, viewing the land as an expendable resource rather than a renewable asset.

The Drive for New Land

The environmental degradation of plantation lands created an urgent economic imperative: planters needed to continually acquire fresh, fertile territory to sustain production and profits.

- This necessity fueled an unrelenting westward push beyond established colonial boundaries.

- The quest for new land was not a peaceful or organic migration but a deliberate, economically driven conquest.

Violent Dispossession and Native Conflict

Westward expansion collided directly with the territories of Indigenous peoples, who had lived on and cultivated these lands for generations. The colonial drive for land led to:

- Systematic dispossession of Native American lands through treaties often made under duress, broken promises, and outright military conquest.

- A series of violent conflicts and wars, such as the various Anglo-Native wars and later conflicts triggered by settler encroachment.

- The displacement and fragmentation of Indigenous communities, whose survival depended on land and access to natural resources.

This expansion was fundamentally a process of colonial violence and imperialism, deeply intertwined with environmental exploitation.

Unsustainable Economic Model

The colonial plantation economy was built on a foundational paradox: its profitability depended on continuous land acquisition because the very crops it relied upon destroyed the land that supported them.

- This model ensured that ecological degradation was built into the economic system’s core.

- Territorial conquest and displacement were not unfortunate side effects but essential to maintaining the profitability of slavery and cash crop agriculture.

Dr. Casagranda’s analysis makes clear that understanding America’s expansion requires recognizing this environmental and economic imperative, a relentless drive for land fueled by ecological limits and capitalist profit motives.

The environmental devastation wrought by plantation agriculture fueled an urgent push westward, bringing colonial ambitions into direct conflict with Indigenous peoples and imperial policy.

3. The Seven Years War and the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The competition over fertile western lands played a central role in one of the most significant global conflicts of the 18th century: the Seven Years War, known in North America as the French and Indian War. Though the war was fought on multiple continents and oceans, its North American theater was defined by colonial ambitions for land and economic dominance.

George Washington and Virginia Elites’ Land Ambitions

At the heart of the conflict was the desire of influential colonial figures, including George Washington and Virginia’s plantation elite, to secure access to rich lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, particularly in regions like Kentucky.

- Kentucky’s fertile soil promised continued growth of tobacco, the colony’s primary cash crop and economic backbone.

- The Washington family, along with other wealthy planters, saw control over these lands as critical to maintaining and expanding their fortunes.

- This ambition was not simply about personal enrichment; it was about securing Virginia’s economic future within the empire.

The British Crown’s Royal Proclamation of 1763

In the aftermath of the war, the British government faced the challenge of managing newly acquired territories and maintaining peace with Native American nations. To this end, the Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which:

- Prohibited colonial settlers from moving west of the Appalachian Mountains.

- Aimed to stabilize relations with Native American tribes by limiting settler encroachment and preventing further violent clashes.

- Established designated Native American territories and promised Crown protection of those lands.

Though the proclamation was a pragmatic imperial policy, it was deeply unpopular among colonists who saw it as an unjust restriction on their economic and territorial ambitions.

Colonial Elite Resistance and Economic Threat

For wealthy southern plantation owners and colonial elites, the Royal Proclamation represented a direct threat to their economic interests.

- Denied access to new, fertile lands, these elites feared the sustainability of their plantation economies was at risk.

- The restriction frustrated their plans to expand tobacco cultivation and maintain profits.

- This discontent among colonial elites contributed to growing tensions between the colonies and British imperial authority.

Seeds of Rebellion and Revolution

The conflict between colonial ambition and imperial regulation created a volatile political environment.

- The Royal Proclamation, intended to pacify Native relations and organize empire governance, instead inflamed colonial grievances.

- It became one of several imperial policies perceived as overreach, fueling resentment that would blossom into revolutionary sentiment.

- Dr. Casagranda emphasizes that this clash over land and economic control planted essential seeds for the American Revolution, linking territorial expansion directly to the political upheaval to come.

The clash between colonial land hunger and British imperial authority over western expansion intensified broader tensions, setting the political stage for revolutionary unrest.

4. Taxation, Representation, and the Revolutionary Spark

The slogan “No taxation without representation” has become emblematic of the American Revolution, often portrayed as a principled stand for democratic rights. Yet, the realities behind this rallying cry reveal a far more complex and economically motivated picture, as Dr. Roy Casagranda highlights.

Minimal Financial Burden, Maximum Symbolic Weight

The taxes imposed by Britain on the American colonies, such as the much-remembered Tea Tax, were relatively modest in their financial impact.

- For the average colonist, the tax on tea might amount to only a few cents per day, a sum unlikely to cause severe hardship.

- Yet, these taxes carried profound symbolic significance, representing Parliament’s assertion of authority over colonial economic and political life without colonial consent.

The British government’s attempt to regulate and tax colonial trade was seen not only as a financial imposition but as a challenge to the colonists’ self-governance and local autonomy.

The Crux: Lack of Parliamentary Representation

At the heart of colonial anger was the fact that the colonies had no direct representation in the British Parliament.

- English constitutional principles, as understood by many colonists, held that taxation required consent through elected representatives.

- The colonies’ exclusion from Parliament meant taxes imposed without their consent were deemed illegitimate and tyrannical.

This perceived denial of political voice galvanized broad sections of colonial society, from merchants to farmers, into opposition against British rule.

Colonial Elites’ Strategic Use of Popular Discontent

However, Dr. Casagranda points out that the colonial elites were not merely champions of democratic ideals; they were shrewd actors with specific economic goals.

- They leveraged widespread resentment about taxation and representation to advance an agenda centered on removing British constraints, particularly those limiting land acquisition and control over enslaved labor.

- The elites saw independence as a means to dismantle imperial regulations that impeded their expansionist and economic ambitions.

The mobilization around “no taxation without representation” thus served as a unifying slogan masking more self-interested motives among the colonial ruling class.

Revolution: A Quest for Elite Economic Control

The American Revolution was, in large part, a struggle for elite control over resources and territory rather than purely a fight for abstract rights or democratic principles.

- The political upheaval allowed colonial elites to break free from British laws restricting westward expansion and the institution of slavery.

- By framing the revolution as a defense of “rights,” they garnered broad-based support while ensuring the post-revolution political and economic order favored their interests.

Dr. Casagranda’s analysis invites us to reconsider the revolution not as a pure ideological moment but as a calculated power shift with profound economic motivations at its core.

While popular grievances over taxation and representation fueled revolutionary fervor, the underlying economic interests of the colonial elite guided the movement’s true objectives.

5. Wealth, Inheritance, and the Economic Reality of Colonial Elites

The popular narrative of early America often celebrates the idea of the “self-made man,” a rugged individual who carved out prosperity through hard work and determination. However, as Dr. Roy Casagranda critically points out, this romanticized image obscures the actual economic foundations of colonial wealth and power.

Inherited Wealth and Plantation Economy

Contrary to the myth of industrious farmers building their fortunes from scratch, many of the colonial elite were beneficiaries of significant inherited wealth, passed down through generations of plantation ownership.

- These plantations were large-scale agricultural enterprises worked primarily by enslaved Africans, whose labor generated vast profits for their owners.

- The value of enslaved people as property and the wealth embedded in extensive landholdings created an economic base that was largely independent of the owner’s labor.

- This wealth was carefully preserved through legal structures like primogeniture and entail, ensuring estates remained intact across generations.

Forced Labor and Legal Reinforcement of Inequality

The prosperity of these families was not accidental or merely cultural; it was built on the systemic exploitation of enslaved people and the enforcement of racialized legal codes that codified inequality.

- Colonial laws stripped enslaved people of fundamental rights and protections, treating them as property rather than persons.

- The legal system upheld and enforced this arrangement, punishing resistance and maintaining the plantation economy.

- Wealth accumulation depended on the unpaid and coerced labor of Black bodies, creating an economic and social order sustained by violence and oppression.

Concentration of Wealth and Power

This concentration of economic resources translated directly into political and social dominance:

- Wealthy plantation owners occupied the upper echelons of colonial society, controlling local governments, militias, and colonial assemblies.

- Their economic power enabled them to shape laws and policies to preserve their interests and limit challenges to their status.

- Social hierarchies were rigidly maintained, reinforcing a system where wealth and racial privilege were intertwined and mutually reinforcing.

Challenging the Historical Narrative

Dr. Casagranda challenges the sanitized versions of American colonial history that celebrate upward mobility and entrepreneurship while ignoring the realities of inherited privilege and systemic oppression.

- This critique invites a more honest reckoning with how wealth and power were and continue to be concentrated in ways that exclude and exploit marginalized groups.

- Understanding this foundation is essential to grasping the roots of persistent social and economic inequalities in America today.

The wealth and power amassed by colonial elites through inherited plantations and enslaved labor laid the groundwork for a new economic system that would redefine human relations.

6. The Birth of Capitalism and a Transactional Society

The year 1776 was a pivotal moment in global history, marking not only the American colonies’ declaration of independence but also the publication of Adam Smith’s seminal work, The Wealth of Nations. Dr. Roy Casagranda highlights this simultaneity as no mere coincidence, but rather a profound convergence that shaped the trajectory of both the new nation and the emerging capitalist system.

Independence and the Birth of a New Economic Order

The American Revolution severed the colonies from British political control, allowing the newly formed United States to chart its economic course. This political rupture coincided with the intellectual articulation of capitalism as an economic system premised on free markets, competition, and profit maximization, as detailed by Adam Smith.

- Smith’s The Wealth of Nations laid the groundwork for economic liberalism, emphasizing the “invisible hand” of markets to allocate resources efficiently.

- This ideology prioritized economic growth and individual self-interest as central drivers of social progress.

People as Economic Units, Not Community Members

Dr. Casagranda stresses that capitalism reframes human relations through a transactional lens, where individuals are primarily valued as economic actors rather than social beings with communal obligations.

- People became workers, consumers, property, or capital, defined by their roles in economic exchanges rather than their citizenship or social ties.

- This shift reduced complex social relationships to monetary transactions, where profit dictated value and worth.

Justification and Perpetuation of Exploitation

This transactional worldview provided ideological cover for ongoing exploitation and exclusion, particularly of marginalized groups:

- Enslaved people and Indigenous communities were dehumanized further, treated strictly as economic resources rather than human beings with rights.

- Economic inequality became naturalized, justified by the presumed efficiency and inevitability of market forces.

- The capitalist framework entrenched systemic disparities by prioritizing wealth accumulation over social justice or equality.

Capitalism and American Political Economy

The birth of capitalism and American independence were thus intertwined phenomena, each shaping the other:

- The new nation’s economic development depended on capitalist principles rooted in exploitation and dispossession.

- The political institutions created post-independence reflected and reinforced this economic order, embedding inequality into the very fabric of governance.

Dr. Casagranda’s analysis calls attention to how understanding this nexus is crucial for grasping the roots of modern social and economic challenges, where market logic continues to shape human relations and policy decisions.

As capitalism emerged alongside American independence, the political system was designed to preserve elite control and perpetuate economic inequalities under the guise of democracy.

7. Political Systems Designed to Protect the Elite

The creation of the United States Constitution marked a critical moment in institutionalizing the control of wealth and power by a privileged elite. Far from being a purely democratic document, the Constitution codified structures and mechanisms that limited political participation to safeguard the interests of wealthy property holders.

Founding Framework Favoring the Wealthy

The framers designed the political system with a clear class bias:

- Voting rights and eligibility for office were initially restricted by property and wealth qualifications, effectively excluding most common people, impoverished whites, Indigenous peoples, and all Black Americans, enslaved or free.

- Representation structures, such as the Senate and the Electoral College, disproportionately favored states and populations with established elite power, limiting the influence of broader popular will.

This arrangement ensured that political power remained in the hands of a narrow socioeconomic class, protecting their interests from populist challenges.

The Role of Campaign Finance and Donor Dependence

In the emerging republic, political power increasingly depended on financial resources:

- Candidates required substantial funds to run effective campaigns, creating a dependency on wealthy donors and special interests.

- This system of campaign finance created a feedback loop: politicians rely on donors for electoral success, and donors expect favorable policies in return.

- Consequently, legislative priorities and governance often reflect the preferences of affluent individuals and corporations rather than the broader public.

This financial gatekeeping entrenched elite influence, restricting political competition and policy innovation that might challenge entrenched economic hierarchies.

James Madison’s Explicit Intentions

James Madison, often hailed as the “Father of the Constitution,” was candid about the document’s purpose:

- In his correspondence, Madison acknowledged that the Constitution was designed to “refine and enlarge the public views by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens,” explicitly meaning the elite.

- He understood that a pure democracy risked empowering the masses at the expense of property owners and sought to construct a republic that balanced popular will with elite control.

- The separation of powers, checks and balances, and indirect election mechanisms were all tools to maintain this balance, favoring the wealthy.

Sustaining Systemic Inequality

The political architecture established by the Constitution has had profound and lasting effects:

- It institutionalized systemic inequality by embedding elite interests into the nation’s foundational governance structures.

- Policies shaped under this system have consistently prioritized economic elites, perpetuating disparities in wealth, access, and political voice.

- Challenges to this order from populist movements to civil rights struggles have had to contend with these deeply embedded structural barriers.

Dr. Casagranda’s analysis urges a recognition that American democracy was, from its inception, a limited and hierarchical system, and that efforts toward social justice must grapple with these entrenched power dynamics.

This deliberate construction of political power ensured systemic inequality endured, highlighting the need to confront these foundations to understand America’s ongoing struggles for justice.

Conclusion

Dr. Roy Casagranda’s scholarship offers a vital and unflinching examination of the deep-rooted foundations upon which America’s economy and political system were built. Far from a narrative of unqualified progress or noble ideals, this history reveals a nation forged through land theft, the brutal institution of slavery, relentless ecological devastation, and the deliberate concentration of power among elites.

These are not mere historical footnotes but structural realities that continue to shape American society today. Understanding this complex and often painful legacy is essential for grappling with the persistent social inequalities, racial injustices, and political inequities that remain deeply embedded in the fabric of the nation.

Dr. Casagranda’s work challenges us to confront uncomfortable truths and reject sanitized versions of history. It calls on us to recognize how economic greed and political power have been interwoven since the very beginning and how only by acknowledging this reality can we hope to build a more equitable and just future.

Call to Action

If this history resonates, I encourage you to explore more of Dr. Roy Casagranda’s work and engage with the ongoing conversations about justice and equity in America. Understanding our past honestly is the first step toward meaningful change.

Acknowledgment and Source Attribution

This article is based substantially on the scholarship and critical insights of Dr. Roy Casagranda, whose research and analysis have profoundly shaped the understanding of America’s colonial history, economic systems, and political structures. The interpretations and narratives presented herein draw from Dr. Casagranda’s public lectures, videos, and written work, which challenge conventional historical narratives and foreground the systemic exploitation and power dynamics foundational to the United States.

While this article is written in an original voice and structured to engage a broader audience, the foundational ideas and framework are those developed by Dr. Casagranda. Readers are strongly encouraged to explore his work directly for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding:

- Website: Sekhmet Liminal

- YouTube Channel: Dr. Roy Casagranda

Proper acknowledgment of sources is essential to academic and intellectual integrity. This article aims to respect and extend Dr. Casagranda’s contributions while inviting readers to engage critically with the ongoing conversations about justice, history, and equity.

Leave a comment